A Reflection for Veteran's Day: From Self-Justification To Responsible Action

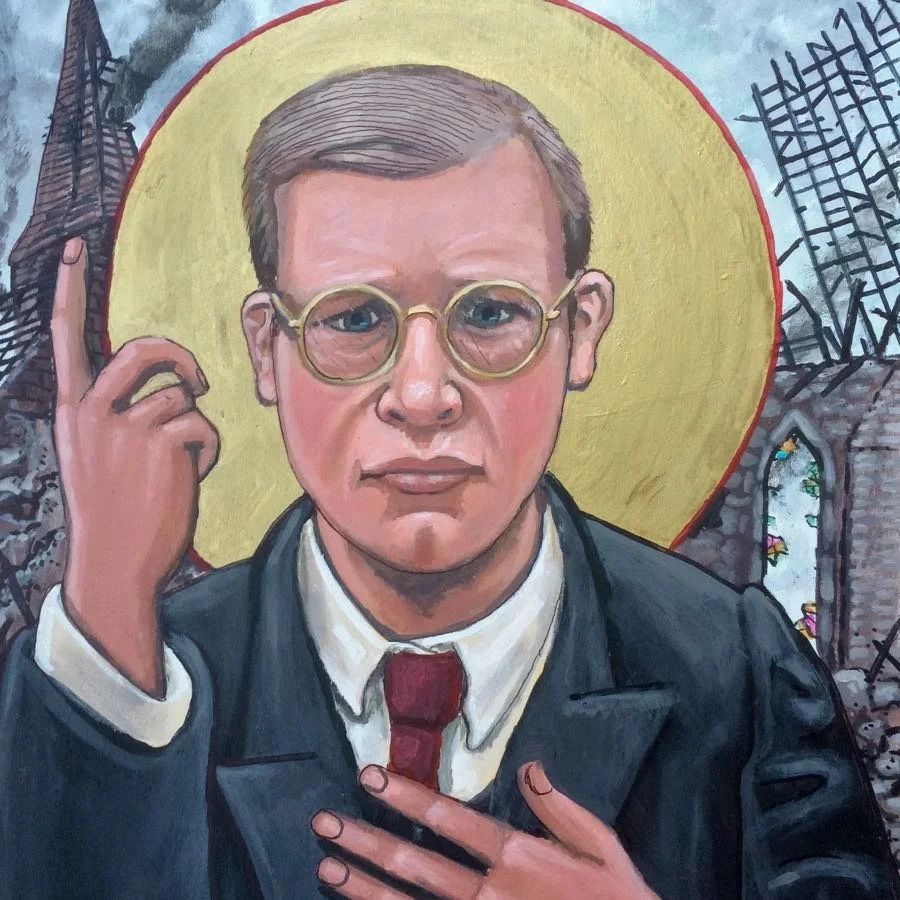

Pulling together the ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the surprising depth of Australian kids cartoon “Bluey”, Vince shares about his complicated feelings around things like Veteran’s Day, as someone who is BOTH anti-military-industrial-complex AND grateful for the way the army saved his brother. (Bonhoeffer Icon by Kelly Latimore)

SPEAKER NOTES

A Reflection for Veteran’s Day: From Self-Justification To Responsible Action

Intro

If you are not a parent of young kids or around young kids regularly, you may not know that some of the finest writing in all of television today is on an Australian cartoon for kids called "Bluey".

It's about a family with two little girls, Bluey and Bingo, in a world where everyone is a dog. The episodes are only like 9 minutes long and I cannot believe how consistently they can make our whole family laugh hysterically AND my wife and me cry from being moved — in that short time span, like every time.

There is this one bottle episode that revolves around a side character, who just for this episode takes center stage: Jack (on the left) is a boy who is just starting at a new school, and you learn quickly in the episode that his family is trying a new school, a new start for him, because he has trouble sitting still, doing what he's told, and remembering things. His parents seem kind, if unsure how to help him, but his little sister embarrasses him immediately in front of his new teacher -- saying out loud: Jack can't sit still, can't do what he's told, and can't remember things.

I wonder if that makes you think of anyone in your life? Or if that makes you think of you? I immediately thought of my brother, James, who died in 2015. But when we were young, he was absolutely Jack. (Unfortunately, I think I was at times Jack's little sister.)

This kicks off the plot of the episode. The teacher introduces Jack to Rusty, a little boy who likes to play "army" (because his dad is in the army) -- Jack asks if he can play, to which Rusty replies: "Can you do what you're told?"

And just as Jack sadly is ready to say no, I'm not good at that, and walk away, Rusty jumps right into play, ("attention!") and Jack jumps in too. And they just start playing "army", and it's cute and funny and silly.

And somewhere along the line, if you're paying attention, you realize that all the imagination games involved in playing "army" have Jack engagingly sitting still, readily doing what he's told, and even remembering things. It's so well written because they don't draw too much attention to it while it's happening.

But at the end of the episode, the two boys, tired from all their play, are sitting and talking, and Rusty asks, "why did you switch to a new school?" And Jack repeats again what he's heard so many around him say "because I can't sit still and can't do as I'm told and can't remember things".

And Rusty, in such a beautiful kid way, says, "oh, well you're really good at playing army".

And it just gets me. It's so subtly done, heartbreaking yet heartwarming. My kids have watched this episode so many times and I tear up every time. DSK off

Because, yes, the episode is about how kids like Jack, like my brother James, can discover they are more than the most limiting stories told about who they are by engaging in play.

AND it's also about how, when those kids grow up, such a common story-theme for many of them is discovering they are more than the most limiting stories told about who they are as adults in the actual army.

This was absolutely the story for James, who had trouble all his life sitting still and doing what he was told and remembering things, but experienced the most validation and purpose and community of his life as a soldier in the army. The army is one of the best things that ever happened to my brother.

Context

How many people have family members or friends in the military?

Yeah, lots of other people I know and love in addition to my brother; he is just always the first person I think of. DSK off

So, switching gears a bit, I wonder if you like me feel discomfort and complexity around this?

Around, for example, things like Veterans Day this Tuesday?

I have the personal experience of my brother on one hand, yes.

But then, on the other hand, I have strong critiques of the global military industrial complex that funds and encourages war and violence for sake of profit and accumulation of power.

As a follower of Jesus, I'm committed to a program of nonviolent resistance, of being anti-war, anti-empire.

So it can feel tempting to distance myself from anything like Veteran's Day.

Especially right now with how militarized ICE is as they’re terrorizing our city, those images can sort of get conflated in my head with veterans and soldiers, and so why would I even want to bring this up?

(PAUSE)

Well, to get personal, for the entire last year since last November, I have, honestly, felt a gentle pull from God, a call to talk about my brother and talk about the experience of people in the military on the Sunday before Veteran's Day this year, to risk the discomfort of that.

Because as much as I want to distance myself from Veteran’s Day, I can never avoid my own brother’s story for long. Or the stories of so many further back in our family histories, whose participation in military contexts I can't just wave away as "obviously all bad".

So I'm responding to my sense of a calling from God this morning. I don't think this is going to be a message that will transfer neatly to an Instagram post. There’s a high likelihood I’m misunderstood this morning. But I don’t want to be driven by my fear of that. I’m going to try to give it a shot.

Stereotypes & Scapegoating

Part of the calling I've felt this last year was hearing an interview with ethicist, theologian, and veteran himself Logan Isaac. slide →

Isaac writes and talks about how most civilians don't really have an accurate picture of soldiers and veterans.

He tries to shine light on the ways veterans experience stereotypes — a hero to be worshipped, a broken person to be pitied, an unmentionable to be avoided, a gun-happy nationalist to be shamed.

Isaac tries to break these stereotypes.

One way is educating civilians about the inner lives of people in the military. For example, about the moral injury they often carry.

Do you know this phrase, moral injury? It has some overlap with Post-Traumatic Stress, which probably most of us have at least heard of before, but it's not exactly the same thing. Moral injury is a psychological, social, spiritual distress that results from acting in or witnessing and not stopping (or being unable to stop) something that contradicts deeply held moral beliefs and expectations — stuff that happens when a soldier is deployed.

It can be feeling guilty and unable to forgive yourself, or feeling shame or disgust toward yourself, or feeling intense anger or a sense of betrayal toward a peer or leader or group or institution.

That’s a much more complex inner life than our stereotypes suggest.

Another way to break the stereotypes is educating civilians about the day-in, day-out experience of being in the military.

Getting to know my military chaplain friend George has helped me with this. George has explained to me the difference between the enlisted working class and the elite officer class inside the armed forces. There's a real power differential there, quite similar to the power differentials many American workers will know as precarious employees downstream from distant bosses and billionaire decision-makers. George has challenged me, as someone opposed to the military industrial complex, to reserve my ire for the highest up officials and politicians in power, not the rank and file soldiers, scientists, medics, and professionals, like my brother was.

So are there some gun-happy nationalists in the military? Yes, unfortunately.

But is that every veteran? Was that my brother? No!

Logan Isaac, from the standpoint of an ethicist, explains that the reason someone like me, a progressive civilian, might resort to stereotyping veterans is in order to offload my own guilt and shame about participating in a military industrial complex with my tax dollars and my American lifestyle.

We all share in that guilt, no avoiding it, but this is a sort of ”at least I'm not like that!" maneuver — slide → one of the oldest tricks in the book to get the monkey off one's back and feel self-justified: blame-shifting, scapegoating.

Instead of stereotyping the common soldiers and veterans among us, assuming them all to be like the worst versions of power-hungry, war-mongering politicians or gun-happy nationalists signing up to work for ICE because they want to terrorize people, what if I sought to listen to and learn from the experience of the common soldier and veteran? slide →

Scripture

From a Christian perspective, there is a way the common soldier or veteran can show us Jesus, the willing scapegoat, vicariously carrying the sin, guilt, and shame of the world on the Cross.

To feel why that matters, we should visit a theological clarification we often repeat here —

For those of us who grew up in religious settings that taught Jesus died on the Cross to satisfy a wrathful God -- that is NOT what we teach here about God and Jesus' death (and that is not actually what the majority of Christians throughout history have taught about God and Jesus' death; it’s just the popular American view of the last 200 years).

The way we phrase it here is: Jesus died not because God demands sacrifice, but because human beings so often demand sacrifice: scapegoats to shift blame on to. In Jesus, God gets the divine hands dirty, stepping in to disrupt that cycle of sacrificing others to justify oneself -- even if that means God’s own self-sacrifice.

This is the "atonement" work of Jesus on the Cross that the scriptures speak to.

Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.

As it was put in John’s Gospel a couple generations after Jesus.

Or, before that, in the letter to the Romans, the church’s first theologian St. Paul wrote

All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and all are justified freely by [God's] grace (we need not obsess over self-justification, sacrificing others!)

[It is] through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus. God presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood—to be received by faith.

But alas we so often don’t receive that by faith. We do obsess over self-justification.

Even further back, in the Hebrew tradition Jesus inherited, there is Leviticus 16's description of the annual Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur in the Jewish calendar), from which we get the language "scapegoat" in its original intention: as a ritual to stop blame-shifting and the sacrificing of others before it starts…

[The Priest] is to lay both hands on the head of the live goat and confess over it all the wickedness and rebellion of the Israelites—all their sins—and put them on the goat’s head. He shall send the goat away into the wilderness in the care of someone appointed for the task. The goat will carry on itself all their sins to a remote place; and the man shall release it in the wilderness.

That’s beautiful! Instead of letting resentment and enmity brew, here’s an "atonement" ritual.

But unfortunately much of the story of the Hebrew Bible, and of all humanity, is a story of refusing to trust -- refusing to "receive by faith" -- what the annual Day of Atonement was meant to represent. scripture off

Sadly, releasing a representational animal into the wilderness just doesn't scratch that human itch for self-justification enough, so we take matters into our own hands and shift blame on to people we've stereotyped, and exclude them, crucify them.

In Jesus, God says, if you’re so hell-bent on crucifying, crucify me. I will enter into your broken cycle and carry the sin and guilt and shame anyway. Because that is what love does.

(PAUSE)

The veteran can show us Jesus, because, in a way, that is what the veteran does — they have entered into that most broken of our human systems, war, to carry the sin and guilt and shame of our world’s violence so civilians don’t have to.

Bonhoeffer

slide →

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the famous WWII era ethicist and theologian who was executed by the Nazis, is someone I quote a lot here, and I want to bring in a quote from him because his ethical reflections are exactly what I'm talking about today -- never oversimplifying or stereotyping, but deep and in touch with the complexity of life.

Bonhoeffer meditated on Jesus in a similar way to what I’ve just explained, as a way to wrestle with involving himself in the plot to assassinate Hitler.

His writings show that he understood himself as vicariously carrying the guilt of his German people by taking responsibility for it -- in his case, responsibility meant knowingly taking on what he regarded as sin (conspiring to kill a person) as a last resort to save millions of innocent people from suffering.

Crucially though, his meditation was NOT to justify himself. His words are not arguing a case before God as to why he's not sinning because the ends justify the means; his whole meditation revolves around what he calls responsible action. slide →

Bonhoeffer fully accepted this was his free choice to conspire to kill and it WAS sin; he believed he had no self-justification to stand on before God, because the real, messy world of genuine evils does not allow anyone to stand pure and guiltless; one invariably gets their hands dirty. And so one can only rely on God truly being a God of love and grace and mercy, as Jesus testified to.

This is a dense passage but read this with me…

When a man takes guilt upon himself in responsibility, and no responsible man can avoid this, he imputes this guilt to himself and to no one else; he answers for it; he accepts responsibility for it. He does not do this in the insolent presumptuousness of his own power, but he does it in the knowledge that this liberty is forced upon him and that in this liberty he is dependent on grace. Before other men the man of free responsibility is justified by necessity; before himself he is acquitted by his conscience; but before God he hopes only for mercy.

Quote off

Obviously the male-centric language is tough, but do you feel the earnest integrity? The humility? Bonhoeffer is writing in a different time, a more duty-bound time, so I get it that it can feel a little bit like we want to rush to reassurance, “dude, don't be so hard on yourself; you’re forced into this; God loves you!”…

BUT… y'all, in our culture, seemingly obsessed with self-justification (and, as a result, with scapegoating), can you see how we need ethical teachers like Bonhoeffer? Not self-justifying, but truly, humbly responsible.

Sure, we have to moderate his intensity for our time, because it can be steered down a bad path toward a theology of feeling like God sees you as a rotten worm, but setting that obvious misstep aside, can you see the incredible, trustworthy quality of humble responsibility in his words? I long for leadership like this!

slide →

The soldier has a window into what Bonhoeffer gives words to that civilians like me don’t know -- the soldier knows the empty promise of self-justification. They know, up close and personal, that everyone's hands are dirty and "no responsible person can avoid this".

For me, as a civilian coming from a progressive starting point, rightly critical of the military-industrial complex, but as a result tempted toward self-justification and scapegoating veterans, the lesson I've learned is:

- I don't get to perform purity and look down on the ones carrying out the violent acts my tax dollars also pay for, simply because I'm farther removed from it.

- I don't get to determine whether or not they are penitent enough.

- I don't get to sit on a high horse, claiming to be more morally righteous.

All of that is about self-justification, and self-justification will never keep me warm at night. It will never help me fall asleep when I'm lying in bed tormented by the ethical dilemmas of 21st century life, or tormented by my own personal regrets and mistakes. Self-justification will never get me up in the morning feeling alive and animated. Because no one's hands aren't dirty.

Closing

What I want to leave us with today is: let us move from self-justification to responsible action. slide →

What is that practically speaking?

When it comes to loving our veteran neighbors and friends and family, it is choosing to be an ally by laying down civilian privilege.

- Check yourself about whether you might be trying to offload guilt by performing purity.

- Instead, how can you listen before speaking? How can you center the experience of those who know war up close, rather than your own discomfort around the topic of war? Can you trust that God is loving and gracious and merciful enough to meet you in the impurity of that discomfort?

- How can you demonstrate a desire to share in the carrying of the burden of guilt and shame the veteran is usually just left to carry themselves for us? Maybe, like Jesus shows us, God is found not in moral purity but in burden-sharing?

- Isn’t this a call that those of us coming from progressive starting points already know well? Ally-ship and laying down privilege? We talk about this all the time with vulnerable populations! Can we put it into practice with our veteran family, friends, and neighbors?

Beyond only our Veteran's Day topic at hand though, pursuing responsible action rather than self-justification is a way of life, practically applicable everywhere.

What if we tried to live out responsible action rather than self-justification with our partners more? With our kids more? With our roommates more? With our co-workers who can be so frustrating sometimes? With our family members who drive us crazy?

With all our neighbors? Even, hardest of all, with our enemies?

One thing I think about is our Prayer of Confession here every Sunday -- the reason we pray this every Sunday is, like we say every time, NOT to be severe or harsh with ourselves. It is to remind ourselves the truth that, in every moment, God offers us what we need to do the hard work of choosing responsible action rather than self-justification.

There is a God of love and grace and mercy who accepts me even when I find it hard to accept myself -- for whatever reason, whatever shame or regret -- personal or collective -- I don’t have to sacrifice someone else to offload my guilt. I can accept that I am accepted, even in guilt. I don’t need to burn myself out trying to justify myself.

No one’s hands aren’t dirty AND YET EVEN SO the most true thing about every single one of us is that we are loved by a God of love.

And THAT is the kind of thing that CAN keep me warm at night, CAN help me fall asleep when I'm tormented, and CAN get me up in the morning feeling alive and animated -- even in the face of genuine evil, debilitating complexity, intense regret or shame -- there is a God of Love who is our companion. slide →